Eric Rohmer is a curious outlier of the French New Wave. I stumbled across his filmography in 2015 after his death in 2010 at the ripe old age of 90. The BFI were paying homage to this brilliantly understated, often neglected French New Wave director. Rohmer went to the Cinémathèque Française with the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Claude Chabrol, but they were well established cineastes long before his career took off. Rohmer’s rise was far more deliberate. He lingered in the background, honing his craft as a journalist before turning to the slow burn of cinema—a journey not marked by the flash and fury of bold proclamations, but by the subtle pulse of restrained elegance.

It was precisely this difference, this quiet rebellion against the bombastic statements of his peers, that captivated me. His films were composed with a meticulousness that suggested a deep contemplation of the everyday—a focus on the intricacies of human dialogue, unburdened by the weight of grandiose themes. In Rohmer, I found a kindred spirit, someone whose work mirrored my own anxieties about the small, fleeting moments of life, the fragments of conversation I feared were too shallow and transient to matter.

Rohmer’s worlds always felt timeless, his films moving with a gentle cadence, unhurried and unconcerned with arriving at any profound conclusion. Although his cinematic breakout came later in life, he was in no hurry to catch up, and his films perfectly capture the indolent narcissism of youth.

Rohmer had some pretty conservative political views, and though he isn’t considered to be a political filmmaker per se, the influence this had on his filmography is evident.

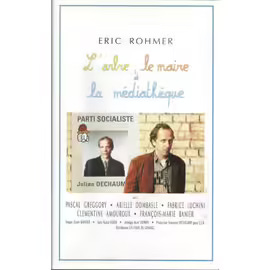

Ecology and preservation are the backdrop for L’arbre, le mayore et le médiathèque (The Tree, the Mayor and the Library) in which the socialist mayor attempts to build a new modern arts centre in a resolutely traditional village. The long diatribes that a local teacher embarks upon against the erection of this so-called ‘eyesore’ of a building are whimsical, a (‘Political Caprice’ according to the New Yorker) but they also capture something of the wholehearted rejection of modern miseries. This is a France that won’t budge, and “why should it?”, Rohmer seems to ask. He clings to a timeless past and the languid pace of his films and their marvellously unspoiled landscapes become imbued with the political.

Rohmer’s filmography is framed by sumptuously idyllic locations which give a sense of eternal holiday. Parisian life is languorous in Rohmer. Work is replaced by long luncheons in outdoor cafes, or conversations in bohemian apartments, and if anyone works, they are an artist. Often however, Rohmer chooses a country or seaside setting; lingering much of the time in the French Riviera, he bathes his characters in the illuminating rays of the sun.

He is much more interested in the anticipation of a thing, “l’attente” (the wait), rather than the big dramatic moments. These micro-dynamics - relations between lovers and friends - are brought to the forefront, and breezy dialogue reaches the height of cinematic tension. His films give space and time for self-realisation - and if that fails, self-reflection.

Self-realisation is the elusive goal of Le Rayon Vert (The Green Ray), the fifth instalment in Rohmer’s series of films titled Comedies and Proverbs. The title recalls the 1882 novel by Jules Verne, which he himself named after the rare optical phenomenon. It is said that at a very precise moment after sunset or before sunrise, a flash of green is visible at the sunset point. A tantalising sight that I have often strained to glimpse, but to no avail. I think it is usually seen only by pilots under very specific conditions. I’m always amused by the frequently cited, though somewhat dubious, claim that the special effects used to create the green ray—which flickers on screen for barely two seconds—ended up costing more than the entire production itself. A character in Rohmer’s film says that “when you see the green ray you can read your own feelings and others too”.

The protagonist, Delphine, could certainly do with some of this clarity. Newly single, Delphine tries to re-orient herself in this world of couples. She is restless, with a deep yearning for something she cannot quite pin down. A string of holidays present themselves to cheer her lonely heart, a group holiday at the beach, an invitation to go camping in Ireland and even a mountain retreat, but none of them are quite what she’s looking for. Delphine is afflicted by a melancholic ennui; her inner turmoil isn’t tragic so much as quietly sad.

Rohmer’s consciously sophisticated characters often fail to notice the beauty that surrounds them, so enveloped are they in themselves. The universal language of beauty is invoked by their supreme physical attractiveness which is a given across Rohmer’s oeuvre. A character in La Collectioneneuse (The Collector) remarks, rather superficially, that “ugliness is an insult to others''. Such self-indulgent musings pepper all of Rohmer’s films but somehow, we are charmed by the unself-conscious vanity. Rohmer dares us to deny the hold that aesthetics have over us as he parades young, bronzed and flawless bodies on the screen. He teases his audience with close shots of various parts of perfect bodies, the images of health and seduction.

Rohmer’s light-hearted films will chase out the winter gloom that is already infringing on September’s autumnal warmth. They are films to watch in the afternoon. The trifling matters of the heart and endlessly pleasant (not to mention, startlingly articulate) conversations are touching. They remind me of summers that one can only experience in childhood, and of an idyllic past I’m not sure that I ever experienced but feels strangely familiar.

I love Eric Rohmer and the scene in A Tale of Winter when she meets the father of her child on the bus made me cry. SPOILER ALERT